LIONHEART – The Legend of Hari Singh Nalwa

Chapter 1 : Hari Singh joins the Durbar of Maharaja Ranjit Singh

*

(See my new story on Maharaja Ranjit Singh: The Maharaja and the Ambassador.)

In the spring of 1804, a young man entered the ancient city of Lahore from the northern gates. Lahore was the heart of the vast Punjab region that swept north western India, from the foothills of the Hindu Kush mountains to the outskirts of India’s ancient capital, Delhi. It was said that Lahore had been founded by Prince Luvuh, one of the twin sons of Lord Rama of Ayodhya, avatara of the Lord Vishnu, the Preserver, one of the trinity of Hinduism’s supreme gods. Now, after decades of war, Lahore was governed by the Sardar Ranjit Singh.

As he entered the gates, the young man, all of thirteen years, dressed in travel stained clothes, would have noticed that the walls of Lahore were in good repair – in some places, as good as new. The gardens – of which there were many, since Lahore had also been the provincial capital of the horticulture loving Mughals – were well kept. And even though it was morning still, the roads were bustling with people wearing an assortment of colourful attire, the men sporting various styles of facial hair. Among them, he would perhaps have been most glad to see, tall, iron studded turbans and long flowing beards – signs of the Sikh Khalsa. For he was a young Khalsa himself, though being only thirteen, it would be while till he got his lion’s beard.

The streets of Lahore, its sights, its sounds, its fragrances were enough to enthral, even entrap. It is unlikely though that our traveler was distracted by the occasional glimpse of a sandalled foot or the flash of a smile from a high, crenelated window, looking down from Lahore’s unique multi-storeyed buildings with wood-carved facades. He was on a mission, a task of utmost importance. On the accomplishment of this duty, rested the fate of his family, his legacy. Unknowingly, on that day, as he walked through the streets of Lahore, we also carried with him the fate of Punjab.

His name was Hari Singh.

*

Hari Singh’s mother had sent him to Lahore. The previous day, he had ridden almost 40 miles, traveling the straight road south from his hometown, Gujranwala to the outskirts of the great capital city. The night had probably been spent in Gurudwara on the outskirts. It would have made sense to refrain from entering a strange big city in the night. Besides, it was in the mornings that Sardar Ranjit Singh held his Durbar, at the Lahore Fort – once the headquarters of the Mughal Raj, now, proudly flying, the triangular flag of the Khalsa, the Nishan Sahib. He was to meet the Sardar of Lahore, to whom his family owed double allegiance, ancient and new.

Ranjit Singh, whom many now called the Maharajah of Punjab, was also the chief of the Sukerchakia faction of the Khalsa – which had once not so long ago been one warring faction of Sikhs, among others, and was now a core of a unifying Sikh army. The Khalsa had once been divided into 12 other houses, known as ‘misals’. The misals ruled various parts of the Punjab, dividing the lands between the Indus and the Yamuna rivers. The Sukerchakias controlled one of the northernmost territories, along the hills of Jammu, bordering the lands of the Afghans, who not so long ago themselves had conquered and ravaged almost all of Punjab, even ransacking Delhi many times. It was from the Afghans that a momentary Unified Khalsa – the Dal Khalsa – had liberated Punjab. On fulfilling the task of liberation, the Unity had shattered. Now, the misals often warred with themselves.

Ranjit Singh would put an end to this. His quest had already begun. It was almost three years since he had conquered Lahore from an alliance of Sikh chiefs. The Sardar of the Sukerchakias was now also the almost universally recognised legitimate King of Punjab – deriving his authority from Akal Purakh, the Eternal One. For Ranjit Singh ruled in the name of the Guru, Baba Nanak and his line, now eternally installed as the eternal, immortal Guru, the Sri Guru Granth Sahib.

Ranjit Singh stressed that he was a regent. The real King was the One True King. And it was in His name that Ranjit Singh would unite Punjab.

But young Hari Singh had come calling to his Sukerchakia Sardar. His father had fought alongside Ranjit Singh’s, as had his grandfather, and perhaps even older ancestors with the old Sukerchakia Sardars.

So, when asked to introduce himself at the gates of the imposing Fort of Lahore, Hari Singh, son of Gurdial Singh, son of Hardas Singh, Jagirdar (Baron) of Baloke, would have introduced himself with pride.

Hari Singh was admitted to the Maharajah’s presence. Ranjit Singh received him with honour and listened to his reason for calling on the Durbar of the Sarkar-e-Khalsaji, the Raj of the Khalsa.

The matter Hari Singh brought before the Durbar was related to his future. It had been almost eight years since his father had died. He had been brought up by his mother’s family. Now there were… problems, as would be expected, since he was almost a grown man. Ranjit Singh understood. He had been orphaned at a young age too. He knew what it meant. So, the young Raja took a decision which would have tremendous consequences for the history of not just his own kingdom, but all of Hind – Hari was taken into the Sarkar-e-Khalsa. He would be the Sardar’s personal bodyguard, a khidmatgar. And there wasn’t much time to settle into his duties, as the Durbar was, within days, moving to the holy city of Amritsar, for dual celebrations – of the the founding of the Khalsa, more than a hundred years ago, and the anniversary of Ranjit Singh’s taking of Lahore.

*

The holy city of Amritsar was home to the Harimandir Sahib and the Akal Takht – the supreme spiritual and temporal authorities of all Sikhs. As a site for worship and pilgrimage, and as a centre of trade and commerce, Amritsar was perhaps the most important city in Punjab. It had been founded in 1574 by the Guru Ramdas, the fourth Sikh Guru. It had quietly grown as a centre of piety and trade for decades, a city of narrow lanes and bustling bazaars, lying as it did at the intersection of the Indian branches of the cross-Eurasian Silk Road trade.

In the 18th century invading hordes of Persians and Afghans ravaged the city time and again. The city of Guru Ramdas recovered.

Amritsar always recovered. Ranjit Singh had taken control of Amritsar only a year ago – after hard fought battles with the misal houses that controlled different quarters of the city. A year ago, each of the houses had their well maintained, garrisoned forts on their respective quarters. They fought, quarrelled and intrigued against one another. One by one, Ranjit Singh had subdued the warring misal houses, taking control of their forts. The last, and most difficult, of these had been the fort of Gobindgarh – the seat of the Bhangi Sardars in Amritsar. The Bhangi misals had once been the most formidable in northern Punjab. That was before the rise of the Sukerchakias.

It was at Gobindgarh that the celebrations would be held. After prayers and offerings at Harimandir Sahib, there would be fairs and games, overseen by the Maharajah of Punjab.

Ranjit Singh was adored in Amritsar. When he had taken the city, and marched through its streets he was welcomed by showers of petals. A similar welcome awaited him no doubt. But when marching from Lahore to Amritsar, the Durbar would have taken its time. After all it was an opportunity to survey the countryside. And the presence of the marching Durbar was always a sure way of asserting authority and signalling to all – there was peace and order in Punjab. A thing to be cherished after long years of troubles.

*

Was it during this march that Hari Singh earned the sobriquet by which generations would know him? It is difficult to say. But if we are to connect some facts about his life, considering especially his meteoric rise at a young age – to follow – and Ranjit Singh’s known regard for having the best men in the best positions, we would not be too off in placing the following story here.

This is the story of how Hari Singh became ‘Nalwa’, the Lionheart.

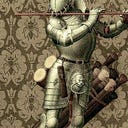

One day, when Ranjit Singh was travelling between cities along with the Durbar, the setting up of camps was delayed due to difficulty in finding a suitable site. The place in which the Durbar found itself as daylight faded was all shrubland. Perhaps while the camp was being set up the Maharaja, always a keen shikari, took the opportunity to hunt some fowl in the sparse forest. Or perhaps he was only wandering, in contemplation. Anyway, his attention was elsewhere and he missed something – a threat lurking in the bushes, a tiger! The tiger would surely have caused the Maharajah grievous harm, but fortune, in the form of Hari Singh, intervened. Armed with only a sword and a shield, Hari Singh pounced on the tiger. And it is said, slayed the beast.

Least to say, in that act of bravery, the boy had saved the future of Punjab, and but for him, the course of history would have been very different. Hari Singh’s bravery had to be honoured in the best way. First the Maharaja bestowed on him his sobriquet – Nalwa – probably derived from the ancient tale of the brave Rajah Nal, from the legend of Nal and Damayanti, comparing Hari Singh’s valour to the grandness of the legend. Or perhaps Hari Singh reminded the Rajah of the folk hero Nal, more popular in the folk tales of southern Punjab as a Robin Hood figure. In the Durbar retinue, another witness to the act, was the court painter Bihari Lal. He was asked by the Rajah to commemorate Hari Singh’s bravery in a royally commissioned painting. So, it could also have been Bihari Lal who likened Hari Singh to Nal, a legendary folk hero of his native land.

Hari Singh Nalwa, this name, however, was to become a legend greater than them all.

(Note: This story is based on an account of a German travelled who is said to have heard it from Hari Singh himself. The Baron met Hari Singh at his residence and saw Bihari Lal’s painting.)

*

Now, we come to the reason for why we placed the story where we did.

At Amritsar, after the offering of prayers and the handling of official business, the Maharajah oversaw a week of festivities, celebrating the holy occasion, the ‘liberation’ of Amritsar, and the change of the season with the festival of Basant Panchami.

The Maharajah himself was a young man, and not averse to ‘committed’ celebrations himself. At the festivities, the Durbar would also oversee the organisation of games where youth from across Punjab would gather to showcase their physical prowess and command of weapons. Ranjit Singh was always keen on overseeing the games himself. Skilled youth would be personally recruited by him into the Army. Also, the incentive for attending the games kept the youth of Punjab committed to training and physical fitness – in times of war, they would all be able recruits, a strong reserve of potential soldiers.

And the time would come. Sooner rather than later.

This time Hari Singh did not wait for chance to give him another opportunity. While he had lived at his uncle’s house, he had not only spent the years learning the holy Gurmukhi script and the Gurbani (the word of the Guru), he had also trained in archery and advanced horse riding. (He had also studied Persian during these years, a language not many Sikhs learned, but which due to the contingency of the age was the official language of the Lahore Durbar.)

Once impressed by his bravery, Ranjit Singh was doubly impressed by young Hari Singh’s skills. He took an important decision. Hari Singh would no longer serve as a khidmatgar. He would train with the Army – the elite corps, the Fauj-i-Khas. And he would do so by leading a regiment of young recruits, a cavalry corps, named after the young man – the Sher Dil Regiment, named for the leader, Hari Singh Nalwa, the Lionheart.

*

Hari Singh Nalwa’s rise in the Lahore Durbar had been meteoric. But not entirely unprecedented. The Maharaja was building an empire, on the ruins of a shattered, divided land. He was always on the lookout for brave, skilled young men, who would owe their allegiance to him, and stand by him in the most difficult, challenging of circumstances.

Hari Singh Nalwa had been chosen on the basis of his bravery and skill. The bravery was his personal quality, the skills honed through years of training. But he was still not a soldier. His teenage years had seen him grow into a man, and claim the legacy of his father. Like his ancestors, he was to fight alongside the Sukerchakia Sardar, now the Maharaja of Punjab, a man destined to take Punjab to a Golden Age. In the making of that destiny, Hari Singh Nalwa was an able partner.

*

About 30 miles south of Lahore, lies its twin city – in a literal sense – Kasur. While Lahore was founded by the ’elder’ twin son of Lord Ram Chandra of Ayodhya, Kasur was founded by Prince Lavah’s brother, Prince Kush. It was during the conquest of Kasur that Hari Singh Nalwa would see his first major battle. This was to be in 1807.

In the two intervening years, however, Hari Singh remained close to the Maharajah. In 1805–6, he had accompanied the Maharaja during diplomatic negotiations between the Maratha ruler of Central India, Jasvant Rao Holkar, and the English East India Company.

Holkar was ruler of vast swathes of central India, from the south of Delhi to northern Maharashtra. The East India Company had by the beginning of the 19th century after gaining hegemony over south and western India been engaged in constant struggle with the Holkar. After a defeat in battle, Jasvant Rao had arrived in Punjab, in hope of an alliance with the Sikh states which ruled the land. The most powerful Sikh state was, by that time, Ranjit Singh’s Lahore. After intense diplomatic negotiations, and arguments for one side or another within his own court, Ranjit Singh had decided not to take sides in the conflict, negotiating instead a Treaty between the Marathas and the British. (The Treaty did not hold.) We can imagine how this high stakes diplomacy would have influenced Hari Singh’s young mind.

Before we move to the Battle of Kasur, it would be helpful to briefly survey the geopolitical map of India at the turn of the 19th century.

*

The Mughal Empire had ruled over most of India from the 16th century onwards. By the middle of the 18th century it had almost collapsed. The Marathas had begun as rebels in the late 17th century and they now controlled most of central India. The peripheral provinces had more or less become independent. Some began to be gobbled up by competing European powers. In the mid 18th century two final blows finished the Mughal order – Persian King Nader Shah’s invasions from the north, and the British East India Company’s conquest of Bengal in the East. The Mughal Emperor would remain in his Durbar for a century more! But he was to be a puppet of this or that power.

While the British grew dominant in the East and South, and the Marathas controlled central India, the north fell under the sway of the Afghan King, Ahmad Shah Abdali ‘Durrani. Abdali had been Nader Shah’s general. After the death of his King, he had broken off with the successors, and taken over the eastern half of the Persian Empire, most of modern day Afghanistan. For two decades, till the 1770s, Abdali continuously raided India. The Mughals had all but retreated from the Punjab, the land that faced Abdali’s wrath. The only resistance he faced was from the Sikhs. (The Marathas too had entered Punjab momentarily. But they could not build alliances or adapt to Punjab’s geopolitics. After a crushing defeat at the hands of the Afghans at Panipat, they retreated to Central India.)

Abdali was a ruthless but formidable empire builder. He founded the Durrani Empire ruled from his seat in Kabul. He was the first Afghan King, native to the Afghan homeland, to rule over the lands of the Afghans in centuries. Ahmad Shah, thus, was the founder of Afghanistan. Afghanistan’s nascent empire in India, mostly Punjab and Kashmir, did not last long. By Ahmad Shah’s last years he had all but given up on reviving his control over lands beyond the Hindu Kush. Every attempt to do so earlier had been thwarted by Sikh armies, and with too many wars on too many fronts, he gave up his ambitions.

A few of his vassals remained in Punjab and Kashmir though. His successors attempted to draw them into an Afghan Empire again, most notably Shah Zaman. Shah Zaman carried out multiple invasions in India, but he was ultimately defeated by the Khalsa. While he had lost control of Lahore years ago, it was from him that Ranjit Singh extracted claims to the city. In his final years, Shah Zaman was dethroned by a conspiratorial clique in Kabul. He was blinded and exiled. He spent his last years under Ranjit Singh’s protection in Lahore. Not the last exiled Afghan King to do so.

If we were to map the sovereignties of this vast land south of the Hindu Kush range, it would be very different from our current representation of block coloured territorial maps, in the political geography section of our books. The region would resemble a jigsaw puzzle, with the pieces of different sizes. Most of the Punjab region would be different hues of blue, the colour most associated with the Khalsa. While identifying with one another as fellow Sikhs, these pieces too constantly clashed with one another. Let us give a darker hue to Ranjit Singh’s piece. This colour had now spread from the Lahore-Gujranwala axis eastward, through Amritsar to the foothills of the Shivalik Range. To the south were multiple pieces, in different hues of blue. These were the other Sikh kingdoms, most importantly Patiala, Jind and Nabha. South of these, along the Jamuna River, on the outskirts of Delhi were small principalities ruled by local lords, including Jats. Then, of course there was Delhi, governed by the Mughal bureaucracy from the Emperors’s Durbar.

Along the eastern swaths of these statelets, ran the foothills of the Himalayas, including the Shivalik and the Kumaon and Garhwal Hills. East of Delhi, along the foothills was a small kingdom of expatriate Afghans, known as Rohillas. Beyond the kingdom of the Rohillas was the Gurkha kingdom of Nepal, dominating the high hills between India and Tibet. South of the Rohilla kingdoms, most territories were under direct or indirect control of the British.

The Gurkha kingdom spread over the hills westward, skirting Rohilla lands, leaving a final piece that lay between them and Ranjit Singh’s territories – the hill state of Kangra.

In 1805–06, Gurkah armies led by Amar Singh Thapa marched across the hill frontiers, threatening to take the formidable Kangra fort in the capital of the hill state. The King of Kangra, Sansar Chand, dispatched his brother, Fateh Chand, quickly to seek help from Ranjit Singh. While Ranjit Singh had skirmished with Sansar Chand in the past he could not have allowed the powerful Gurkha Kingdom to consolidate its hold at the doorway to Punjab. The Maharaja rushed the Khalsa army up the Shivalik hills, relieved the siege of the Kangra Fort and pushed back the Gurkhas.

With the Gurkhas defeated Sansar Chand was quick to pay tribute to the Maharaja of Punjab, and Kangra too turned into Ranjit Singh’s hue, becoming a vassal state. (Impressed by the bravery of the Gurkhas, Ranjit Singh hired Gurkha soldiers into his army and organised them into a Gurkha regiment.)

As we can see, the regions of Northern India were a confused mess of competing sovereignties. Ranjit Singh’s empire building would bring order to the region. Controlling the swathe of land from Gujranwala to Kangra put him at the heart of the northern subcontinent. This was a position of potential, of both opportunities and threats. The Sikh states to the south were wary of him but would not present a military threat. After taking control of Kangra he had eliminated the Gurkha threat from the west. The Rohillas were no threat – the smaller Sikh states and independent bands of Khalsa warriors were more than enough to contain them. In time, the Rohillas too came under British protection. For a while the frontiers of their land were open to contestation. But quickly this land too was subsumed under the rising English imperial order.

Now, moving to the west. This was where the greatest threats to Ranjit Singh lay. After taking the claims to Lahore from Shah Zaman, the Afghan threat had more or less abated. The Afghan Amirs had reconciled to the fact that their Indian Empire was lost. They still nominally controlled Kashmir. But Ranjit Singh’s territories cut like a knife through the routes that connected Afghanistan with Kashmir, that is, through the passes of the Hindu Kush to Jammu and onwards. So, Kashmir too had descended into a disorder of warring Afghan chiefs and resurgent Hindu ones. It was no threat.

The core of Ranjit Singh’s territories around Lahore and Gujranwala were, however, exposed. All along the swaths from the north west to the south, various small territories centred around strong, garrisoned forts were controlled by independent Afghan chiefs or remnants of the Mughal aristocracy.

The nearest – and most dangerous – of these was Kasur. The rulers of Kasur had been fought and subdued before. They paid nominal tribute to Ranjit Singh. But it was a tense, unstable relationship based on mistrust and hostility. Ranjit Singh describe Kasur as a knife aimed at his back.

While camped at the volcanic city of Jwalamukhi in the Kangra hills, the Maharaja received news that trouble was brewing in Kasur. An army of Ghazis – religious warriors vowed to fight till the death – had gathered, teeming thousands, at the fortress of Kasur. The Ghazis led by the Nawab of Kasur were ready and eager to strike at the heart of their enemy – the capital of the Sarkar-e-Khalsa, Lahore, only 30 miles to the north. With most of the Army returning from the Kangra campaign Lahore was more vulnerable than ever.

The insurrection of the Nawab of Kasur and his Army of Ghazis was an existential threat to the empire. A dagger aimed not at the back, but the heart.

***

Please subscribe to my newsletter to receive latest articles in your email inbox: https://sialmirzagoraya.substack.com