Last Ride of the Tigerslayer (Part 1 of 3)

Day 1 of the Battle of Jamrud, April’s End, 1837.

As the chill of spring gave way to summers heat, a storm was brewing in the desolate highlands beyond the Hindu Kush, gathering force to break across the mountains which were known from ancient times as a graveyard of Hindus, as men, giants in form and strength, from remote mountain fasts, from the deepest hidden crags, answered the call of Amin-ul-Momeen Dost Muhammad Khan, Amir of Kabul and the Armies of the Empire, swelled by those who had answered the call of Jihad, approached the fields of Peshawar to attain martyrdom, prepared to slay, plunder and destroy – for God.

As the heavens roared in anticipation of the greatest battle to be fought on the frontiers of Hind since ages past, the Army of Kabul, led by Wazir Akbar Khan, with four of his brothers : Afzil Khan, Azem Khan, Haidar Khan, Akram Khan, all sons of the Amir; with nawabs and mountain lords in tow, they made their way through the crags and crevices, and secret paths, gathering force as the dwellers of the old passes slunk out from their secret caves to march under the green banner. Still more units would soon join the invading force in the coming days, they would be joined soon by bands of warrior Ghazis led by. Jabar Khan, Osman Khan, Sujah Dowlah, Shamsadin, Akhunzada, Mulla Momind, Hussen Khan, Arz Begi, Zerin Khan, Nazir Dilawar. Warlords all answering the call of Jihad. They would come. For glory, death and paradise.

Far in the distance, in the middle of an open plain at the foots of the tall, bare mountains stood a fortress flying the Kesari banner of the Khalsa. For decades, the infidel Sikhs had warred with the Afghans, Turks, Qizilbashis, Uzbeks, Khybairee, Afridi, and a thousand more tribes, they had wrested inch by inch from the Kingdom of Kabul, from the exalted Throne of Thousand Tribes, the homeland which had once been theirs – but whose watan was it really? Hind had been won by the sword, of had been lost to the steel-wielding Sikhs, risen from the dust, once peasants clothed in jute rags, now warrior-kings – a bane upon the Afghan nation. They had begun by gnawing at the edges of the great Baba Ahmad Khan’s empire, and now sat as rulers of first Lahore and then Peshawar, the city in the midst of a verdant vale, abounding in the beauty of kudrat and the wealth of a thousand Silk Road caravans – once the pearl in the crown of the Durrani, now a thorn in every Afghan heart.

Wazir Akbar Khan had vowed to end the era of shame and reclaim the grand city, once the summer capital of the House of Dur-i-Durrani, and bring glory back to the Throne of a Thousand Clans. Only some seasons ago the Ameer his father Dost Mohammed Khan had tried and failed, had led a campaign planned meticulously for years to wrest the city and the vale. The vast Armies of the Ameer-ul-Islam had been shattered by the One Eyed Lion who haunted the dreams of every Khan from Kabul to Bokhara. Ranjit Singh. Ranjit Singh. Ranjit Singh. They shouted waking up from fevered dreams. The One Eyed Devil who was prophesied to destroy the House of Islam, he sat on the Lion Throne of Lahore.

Fifty thousand tigers were shattered by one battalion of Sikh guns commandeered by the Lion is the Battle of Peshawar only two years ago. Fate had not favoured the Afghans then. For had not the spies from Kashmir reported the Fauj-i-Khalsa would be led by that pig Ventura. Who knew the Lion was lurking only miles away with another force. The Sikhs had been all but broken, when Ranjit Singh reached the camp and turned the tide. Dost Mohammed had fled from another battle against these dogs of hell – again, yet again.

How many times would the Afghans face defeat from these upstarts – had the One God forsaken them?

Seventy years ago the grandfather of Lahore’s One Eyed Lion King, one Charattu, had fought the forces of Baba Khan – with another upstart, Jassa Kalal, he had chased the Grand Army of Imperial Afghanistan from the Sutlej to the Jhelum, not allowing the camp one good night of rest, so thousands of weary souls, too weak to swim against the fast flowing mountain stream, had been washed away into watery graves. Only three years after the Durrani had thought the Sikh rebels would forever be crushed after their Temple was destroyed the upstart dogs had dealt this deathly blow. A weed that is left to grow in a garden corner should be plucked from the root lest it run rampant with time. Baba Khan had fought too long on the Uzbek frontier, and had ignored the real enemy within.

Akbar would not fail. Akbar Khan would be the new Ahmad Khan, the blood of Abdali was strong, coursing like fire in his veins, a fire that would fuel the dawn of a new dynasty – first Peshawar, then Lahore, then razing Amritsar to the ground like the dogs had reduced Sirhind, then on to the plains of Delhi. Then, Calcutta. And with the firangi ships under his control the world would bow to a new era of Dar-ul-Islam. Banners of the faith would flock to him, a new era of conquest for a new age of glory.

The Army of Islam gathered on the plains of Jamrud. The fortress would fall, and the Kesari banner that gleamed golden even in the night, would roll in the dust of Akbar Khan’s feet.

–

The last hour of the night faded into the Ambrosial Hour. Lions stirred awake.

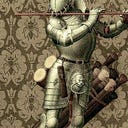

Glory was called to the One, as one more day began in which every Khalsa who had taken up the steel band and the blue cloth, hoped to die in glory and mingle with the essence of Akal’s Timelessness. Sardar Maha Singh recalled what his father had said when the janeos of their family were replaced with the strap of the kirpan – now we have embraced a new path, my son, now we laugh in the face of death.

Death. Death. How would death come? The morning prayers gave him comfort. But the thought of death lingered in his mind, even as purple dawn cracked over the cragged crests of forlorn peaks.

It was still half an hour to first light when he heard Ajab Singh’s footsteps, distinguishable by his fumbling walk. The man was still nursing the after effects of the night’s revelry.

‘Sat Sri Akal Baba Randhawey, what news from Peshawar?’

The grizzled soldier returned Glory to the Immortal One before handing Maha Singh a parchment. A messenger had ridden relaying from Peshawar a message in the middle of the night, like every night, carrying news of the city gripped by cholera.

Maha Singh read with trepidation.

‘It says nothing of Baaghmaar.’

‘His fever still rages, I am told.’

‘The the walls of the Empire are weak.’

‘We are the walls of the Empire, Maha Singh. And Shankargarh and Michni. The work on the frontier forts took a toll on the great man. He must rest, and we, we watch the passes of the blood mountains.’

The first glow of sunlight began to seep up into the edge of the sky’s upturned bowl.

The dawning day was more strangely all too silent.

‘So, we should not expect any reinforcements from Peshawar today?’

‘Not likely, friend, since the letter you sent to Lahore are now in the vaults of Srinagar.’

‘The Lion does not expect Dost Mohammed’s intrigues now, since he was routed two years ago, it is said the Ameer is a broken man,’ Maha Singh said, perhaps trying to ignore talk of the intrigues in the court of Lahore, too uncomfortable for a straight military man.

‘There is something else I have to tell you. I have heard a rumour. The Prince, Naunihal Singh, after the wedding vows are affirmed, perhaps he hope to march, perhaps… north,’ said Ajab Singh even as he was interrupted by a young khidmatgaar’s cough from behind them. A young Bhujangi, beard like iron wires sprouting from his chin, whiskers turned up like curved swords, fires burning in his eyes.

The young man hesitated, perhaps he wished to speak.

‘Say what you will, young Khalsaji,’ Maha Singh said gently.

The young man spoke hesitatingly. ‘The… the prophecy… I mean… that one day the Khalsa’s banners will be paraded through the streets of Kabul.’

‘Perhaps…,’ Maha Singh began to speak but a sound interrupted his words – the mournful wail of a Khaibaree warhorn. A raid.

Ajab Singh Randhawa walked away hastily to don his arms, hand on forehead. It would be a difficult day for him.

–

Harsharan Kaur had heard the wailing cry of the. Afghan warhorn before. On the evening so many days ago when she, along with her father and aunt, had approached the walls of the looming fort she had heard the sound. It had petrified her.

Now, she knew it was probably a distraction rather than an actual assault on the Fort. But she was thankful the sound had woken her up from sleep. There was so much work to do, keeping house for her brothers, as they guarded the frontiers of Punjab. Sometimes she wished she was a boy, a soldier, a Khalsa, a warrior. But those moments passed. She had seen wounded men, and once, a dead man in the few days she had been at Jamrud. The soldiers needed the spiritual strength her father, the Grunthee, provided them, and her father needed hers. When her father had been appointed as the priest of the Gurudwara in the Fort, she had insisted on coming along. He was an old man, and someone had to care for him. Bhua was old too and for how long could she look after her brother. They had, unwittingly, agreed.

Caring for her father have meaning to her life. The Gurudwara of Jamrud was the source of strength for all the soldiers posted there – her 800 brothers. On Rakhri, she had tied one bond to Sardar Maha Singh’s wrist and another to the iron bolt at the gate’s strong door, like all the woman sevadaars of the Fort had done.

‘Some people say the Rakhri is a promise by brothers to protect their sisters, but what is more important is the blessings of the sister protecting her brothers on the battlefield. You, my brothers, as you stand tall against so many storms from the north, may all my prayers be for you and the walls of Fatehgarh.’

She smiled as she thought how eloquent she had been that day, but… another wail of the war horn.

There was commotion outside. The soldiers were gathering in the central yard. Some shouting, some hurried feet and in the distance, a shot from a gun.

This was more than a raid, Harsharan Kaur thought to herself as she prepared her mind for the coming day by repeating in her mind the name of the Immortal Unborn One.

–

As the sun crawled up into an higher perch in the east, as if eager to get a glimpse of the epic battle soon to rage below through the thin cover of clouds, Maha Singh realised it was more than a raid. The tribes of the passes, they brought no guns, in their raids. This was the advance force of a larger army, perhaps holding back in. hidden defiles, waiting to march forward when the walls of Jamrud were breached.

Perhaps ten thousand had taken positions in the field that extended outside the fort. Sikh guns had been raining down on them for hours, forcing them down. Perhaps the Khalsa forces could hold out till word reached Peshawar and the Frontier Force – all that remained of it – marched out from the garrison. The Pathans would not know they weren’t led by Baaghmaar – every child in the frontier possibly knew he was sick and confined to his chambers, by now – but even then, just word of an approaching Khalsa Army would be enough to make the mountain tribes flee.

Jamrud would hold even if it was more than a raid. The walls had been strengthened since the last battle, a well had been dug and the storehouses filled with grain, powder and steel.

There was an explosion in the northern wall. Not just thin barrel guns, they had cannons! That changed things. Another explosion.

Maha Singh called out to his young khidmatgaar, Sher Singh. ‘I want half the men on the walls… now… down… sand in sacks. On it. Get as many bags ready as they can.’ Yet another strike on the ramparts and a shower of rubble struck Maha Singh. They would need to reinforce the walls sooner.

But who had expected the tribes would march down with guns! The Baaghmaar had raised the idea of the Ameer equipping then for more damaging raids. He had warned the Sarkar, in letter after letter that the frontier force should be strengthened, the tribes smoked out from their defiles. But all they had received was a letter from Hira Singh that he, as Prime Minister, had things under control – through diplomacy. Diplomacy! What good was diplomacy now!

Maha Singh himself scrambled towards the steel ladder to climb down from the ramparts. He passed a group of wounded men, nursing their own bleeding limbs. They had been guards on the tower which had been struck.

‘Stay strong, Singho, looks like we have a long day ahead of us,’ Maha Singh said giving the three of them a pat each on the back. Two of them were grizzled men with grey in their flowing beards, one, a young man whose beard was yet sprouting.

‘And what is your name, Bhujangi?’

‘Prem Singh, Sardarji. Sat Sri Akal!’

‘Sat Sri Akal Prem Singh Sardarji. Now, listen carefully, first tell me how badly are you hurt?’

‘Just a scratch, Sardarji,’ he said as the two older men chuckled.

‘Good. Once you’re patched up, I want you to go down into the armoury. And get me a report of our stocks. Be careful with your reports, I want one every hour from you. Understood?’

The young man nodded. He was only slightly grazed on a forearm and his left cheek. Maha Singh remembered him as a Sikligar Sikh who had joined the Jamrud Force last month.

After sharing a few words with the other two Singhs, Maha Singh proceeded down the ramparts. It was bright morning now as the crimson of the morning had given way to a vermillion hued blue. Across the plain, just beyond the range of the Fort guns, more Afghans had assembled. These weren’t just regulars. The gun which was firing on them was placed some way away from the main body, on slightly elevated ground, sheltered by a copse of trees. It was placed to distract fire from the Sikh guns, allowing the besiegers to inch closer to the fort. A trap.

As he descended from the ladder into the yard, where groups of men, and some women – the caretakers of the housing quarters – were drawing water from the well he heard another sound. The peeling call of the shanknaad.

Baba Kehar Singh, a veteran of the Akalis, was sounding the conch-shell, standing on an elevated platform in the yard. The old Baba had fought the greatest battles alongside the great Baba Phoola Singh Akali. He wore his battle scars from Naushera with pride. But he had often spoken to Maha Singh of his misfortunate he had been to have been so close to the greatest shaheeds without once attaining shaheedi!

There were thirty Akali Warriors in the Fort. Thirty. A good number.

And ten thousand Pathans, perhaps more, out on the plains. If the Baba was ready to march towards his destiny, how many hundreds would fall before fortune finally favoured the old man.

–

Thirty riders stormed out of the fort, their blue cloaks streaking like broken stars in a fortuitous sky, iron clanging in rhythm with thudding hooves, as the stage awaited a glorious dance. When cries to the glory of Immortal Akal rent the battleground, a palpitation shook the air in the Afghan ranks, as a momentary stench filled the air wafting in from the Afghan side. The grounds were moistened with more than the slight drizzle which showered from the pearl-hued sky.

A dance was danced, as clouds of crimson sprayed into the April air, a deva watching down from Indra’s abode, if he woke from an ancient slumber, would have thought it was the colour festival of Basant in the streets of Lahore. The barren ground in the shade of the Hindu Kush was so soaked in blood that luscious meadows would spring out in the fields of Jamrud after the rains. The air was livened with the songs of death as the thirty Akalis slew many hundred Afghans before mingling their souls into Timelessness, leaving, one after the other, their bodies behind in this realm of dust.

–

The charge of the Akalis had given an opportunity to Maha Singh to take out the gun striking at them from the sheltered copse.

Ajab Singh was more than eager to sally forth into the battlefield. There was not a Yusufzai this or that side of the Khyber who knew not the name of his grandfather, the great Dal Singh Randhawa. It was time for the grandson you follow the family legacy of giving the Pathans a besting they would remember for generations.

‘As Babaji strikes into the main body, hoping to cut through and rally around,’ Ajab Singh had said, ‘we will launch a second sally towards the gun. Most of the guns will be firing on the main body of the Afghans, I’ll need two guns from the north-western ramparts to cover me – and hopefully in within an hour we will have captured their damned gun.’

That, at least, had been the plan.

Maha Singh watched from the walls as it went awry. Even as Baba Kehar Singh and the thirty Akalis were wreaking havoc in the Afghan ranks, he watched as a contingent of Afghan jezail shooters launched volley after volley on Ajab Singh’s twenty riders. The trees! The snipers were in the trees. How long had they been there! Perhaps since the middle of the night.

The charge of Ajab Singh’s riders was broken as seven of them fell. Two more had their horses severely wounded. They jumped off, and began to approach the copse crawling towards it! The brave fools, Maha Singh thought.

Ajab Singh had been struck in the thigh. He rode on. In minutes the remaining riders were in the midst of the copse. Pistols were fired, swords clanged and finally there was silence. The two Singhs who had been crawling towards the copse reached it now.

Maha Singh watched as the Singhs entered the copse and emerged a while later, leading two horses each, with two wounded men on the back of one, and one on the other. This one was Ajab Singh.

Still alive and no doubt yearning for a swig.

–

As the sun climbed towards its noon perch, still some way away and shyly glowing behind the veil of clouds, a message was dispatched to Wazir Akbar Khan who had just woken from rest after the long march through the night and was yet to rub out the dreams of glory from his eyes – the first charge of the day was broken.

The Battle of Jamrud was at risk of being lost before it even began.

–

‘What! Broken, shattered, lost! These Yaghistani mountain rats have the gall to call themselves true Pakhtun! How much money had Sami Khan poured into their filthy pockets. Every penny gathered from the kafirs of Kabul. You know how many Hindu merchants have fled from Kabul complaining of my … ah, my father’s extortionary ways… the Grand Market of Kabul will be empty for years. We might as well burn it down.’

An enraged Akbar Khan lashed at his lieutenant, his soldiers. watched in amusement. One of his bastard brothers from his father’s unspoken of days, a snickering wretch, caught his eye, a disgusting effeminate creature, a known defiler of boys, as it was, this time he had caught Akbar Khan in a bad mood.

‘You will lead out half our forces. There are seven guns on the battlefield, take three more. Take command of the Yaghistanis. I want to walls breeched before we are joined by Afzil Khan and the others. I will take command of Jamrud before dark, you understand.’

‘Brother, I…’

‘Go… and, peace be upon you.’

–

After half an hour he received news that his bastard brother was dead. Many a childhood was saved from ruin. Another sally from the fort. How many men did they have inside? His spies had said not more than a thousand, so if…

‘The Khan approaches,’ a khidmatgar announced.

The noble figure of his blood brother Akram Khan approached, followed closely behind by the younger, Azem Khan, the ever present smirk on his face. Some day Akbar Khan would wipe it off with a dagger.

‘I thought you would be preparing for our welcome feast in Jamrud, Wazir Akbar Khan, not meeting us here, like a …’

‘How many men have your brought me?’ Akbar Khan said ignoring the man’s tone.

‘Enough… unless…’

‘Unless what…’

‘Unless they have Baaghmaar – is he in the field.’

Akbar Khan momentarily felt the grip on his sword loosen.

‘He is… on the verge of death they say,’ Azem Khan added, slyly.

‘Good. May Allah send him to the fieriest circle of hell,’ Akram Khan said, continuing, ‘but we cannot wait while the… dogs remain holed up behind their walls. We have seven more guns. We need to take Jamrud.’

Akram Khan was a practical man. The man for the job.

‘Go! May the blessings of Allah be with you. And… you may take three guns. We will need the rest for the walls of Peshawar just in case… have you heard from Brother Haidar?’

Akram Khan grumbled under his breath and spat a phelgmy glob before speaking.

‘Yes. He and Sami Khan will be here by nightfall. I must tell, all that money wasted on purchasing the loyalties of the mountain tribes… you cannot buy that with any amount of treasure what seller has not to give. Besides, I think he’s just pocketed it all. We should have spent the money on… other parties. In Lahore.’

‘Once we take Peshawar, brother, our coffers will overflow with wealth again. Thankfully, we know there are many loyalties for sale in Lahore, or should I say, Kashmir.’

–

‘You think they hear us in Peshawar,’ young Karam Singh asked his partner Gujjar Singh as they loaded the swivel gun mounted on the northern rampart.

‘Maybe, if the wind blows towards … what do you think you are doing!’

Karam Singh had climbed up onto the parapet wall, a tuft if straw in his hand.

‘Checking the wind,’ he said. As he released it, the wind carried the tuft north. Towards the mountains and away from the direction of Peshawar.

In the armoury below, Maha Singh had much to think about. The two sallies had reduced their numbers. They had lost fourty men. A rescue party had returned to the copse to bring back the wounded and dead. The bodies of the Akalis had been taken by the Afghans. Perhaps an arrangement could be made to bring them back in the evening. The rescue party had brought back two Afghan prisoners too wounded to talk.

Seven hundred and fifty fighting men and twenty sevadars, including the women, all of whom could take up arms if needed. But now, they had more important things to do – tending to the wounded and shoring up the walls.

Three Afghan guns had been destroyed in the sally of the Akalis. The besieging Afghan forces had been broken and twice they had been reinforced. How many were waiting in the defiles to fall upon Jamrud?

He had to send a message to Peshawar. Maybe another sally. Two parties. One to distract the Afghans, one to flank them, allowing one horseman to ride away undetected.

But how many lives would it cost? How many more?

Ajab Singh Randhawa too was in much worse condition than he had seemed at first. The vaids had been unable to stem his bleeding. The warrior was unconscious now. Only a fool would expect him to make it through the night, but then, he was the grandson of Dal Singh and the son of Kahan Singh – the father had defending the Sutlej fort, would the son become immortal in the defence of Jamrud? But the question was, could Jamrud be defended in the face of such overwhelming force if no succour arrived from Peshawar?

Another sally would have to be made. And a messenger had to be sent to Peshawar, to the only man who could save the fort, the city, the vale and perhaps the Khalsa Raj.

Had not one of the wounded Afghans muttered that another army was striking out for the forts of Michni and Shankargarh? Maha Singh offered a silent prayer for Sardar Lehna Singh, the fort-master of those twin citadels, who would undoubtedly be in a predicament as difficult as his very soon. And much worse if. a messenger didn’t reach Peshawar in time.

–

Jabar Khan saw the smoke rise in the distance. And they had said Jamrud would fall before the sun reached zenith! By the looks of it the battle was still raging. Akhunzada and Mulla Momind rode up besides him.

‘Allah does not favour us, Mulla Sahib,’ Jabar Khan said jestingly.

‘I have had a vision and it can not be wrong. It was Jabrail himself who whispered in my ear, Akbar Khan would have his khutba read by my pious lips in the Badshahi Masjid in Lahore. The head of the one eyed demon rolling at his feet,’ the Mulla said, as if speaking from an old memory.

‘After we have cleaned the dung out of it,’ Akhunzada said smirking.

‘Do not jest about the house of god, or I …’

A gunshot interrupted him. Jabar Khan’s attention was drawn to a cloud in the distance. The forward scouts. They were riding towards him, with… a man. A young Sikh, his long hair disheveled over his face.

‘A messenger, my lord,’ a scout shouted as soon as he was in hearing range. ‘From Jamrud, to… to… Peshawar.’

‘You are afraid to take his name,’ Akhunzada smirked.

The scout neared Jabar Khan and handed him a bloodied parchment.

Jabar Khan flung it back.

‘Whose command do you follow,’ Akhunzada asked, sternly now.

‘Janaab… Arz Begi Janaab…’ the soldier muttered in stuttering Pashto.

‘A Hindustani! And what are you doing so far away from your kaffir home, Hindustani,’ Akhunzada asked, returning to his jesting tone.

‘I… I answered the call, my lord. To rid the land of kaffir rule.’

‘Mashallah! You honour the spirit of Syed Barelvi, my son,’ Mulla Momin exclaimed. He took the parchment from the soldiers hand.

‘If you had cared to attend a madrasa when you were still a gentle hearted boy, Jabar Khan, you would know. This is a message for their commander… Sardar… H… H…’ the Mulla choked.

‘We know who he is, tell me what it says,’ Jabar Khan said, a not very old scar on his left buttock itching from remembrance.

‘That Jamrud is ripe for the taking. I suggest you seize the moment, and make the glory of the day yours,’ Akhunzada who had snatched the parchment from the Mulla said.

‘Pass the orders down the line, we will join the siege instead of making way to the meeting point and…’

‘… and make the fort ours before Akbar Khan defiles it’s grounds with the blood of more Afghans,’ Akhunzada competed.

They rode towards the walls of Jamrud.

–

Harsharan Kaur had been climbing up and down the ramparts, making sure each of her brothers were fed with the partakings of the deg so necessary for the apt wielding of Sir Teg. In the sangat below, her father’s recitation of Jaap Sahib had now extended into Chandi di Vaar.

As she made her way across the yard, she felt a large wet drop on her shoulder. The skies had begun to open.

–

Karam Singh laughed at Gujjar Singh’s crude joke as they saw the Pathans retreating from their positions, as if dissolving in the rain which was now a downpour. The day had darkened with pile upon pile of pregnant clouds, angry lightning sparked silver streaks in the upturned bowl of the sky, as peals of thunder resounding in the air, echoing back from the far mountains, brought to a momentary halt this one day of war of man against man, of tigers besieging lions.

-

In Peshawar, only ten miles away, the rain was still distant, but the cool moisture laden air carried a distinct ferrous strain that the good folk of Peshawar had become used to so they hardly took note. But a man in his chambers, even in his fevered dreams, knew, knew it was the smell of blood.

He stirred.

For a moment the thunder and lightning stopped. It was silent everywhere. Hari Singh Nalwa, the slayer of Tigers, Baaghmaar, the Bane of Afghans. was waking.

–