EVOLUTION OF THE SIKH POLITY

Importance of the 18th Century in Sikh History and the idea of Sikh Raj

INTRODUCTION

When we speak of Sikh Raj in a historical sense, we often begin (and, sadly, end) with the Sarkar-i-Khalsa founded by Maharaja Ranjit Singh. While this is a glorious period of Sikh history, which must be studied and remembered, the glamour of the Lahore Durbar is such that it often outshines the grittier, and perhaps more formative, period of our history, the era of the Dal Khalsa.

The framework of political structures which evolved during the 18th century have continued to remain the architectural substructure of the Sikh polity. Whether the polity has been of confederated territories, whether it has been imperial, or, even when it has been non-territorial. [For most of the early 18th century, the Sikh polity was non-territorially structured, towards the end, it evolved into a confederation, which gradually became subsumed under rival dynastic kingdoms, before taking a final imperial form. There was a brief era of non-territorial sovereignty beginning from the Second Anglo Sikh War, which continued in some way till the 1860s – a subject we will explore in a later essay. In much more detail]

PROLOGUE

In 1884, while contemplating his final break and declared rebellion against the British government, Maharaja Duleep Singh presented a tract – The Maharaja Duleep Singh and the Government. In this document, compiled from his private notes he cogently laid out the illegality of not just the British annexation but also continued occupation of Punjab. The annexation had proceeded from a fundamental misinterpretation of the Sikh political system, in his view. (In mine, exploitation of an intentional misinterpretation.)

While the British had relied on select ministers of the Lahore Durbar – especially the ‘traitorous’ Gulab Singh of Kashmir, his sometime agent, Lal Singh and the General Tej Singh – the agent-in-charge of Punjab Affairs for the East India Company, Sir Henry Lawrence, in Duleep Singh’s view, had failed to take into account where ‘real authority’ rested. In the exiled Maharaja’s estimate, ‘the Punchayats of the army were in fact the representatives of the sacred KHALSA, in whose name Runjeet always issued his decrees’ (pp 29–30). The decrees of Maharaja Ranjit Singh were issued in the name of ‘Khalsaji’, of which he was a mere representative. [Interestingly, Ranjit Singh did not wear any crown, only wearing the Kohinoor diamond on singular occasions – a sign of his subjugation of the Afghan throne; he never sat on a throne himself, which was usually left empty in court, symbolically occupied by the Akal Purakh, the ‘true emperor’, sacha padishah, of the Sikh nation.]

So, even for Maharaja Duleep Singh, someone who had been kidnapped, forcibly trained out of his religion and culture, it was quite clear what the source of Sikh power was.

It resided in the body politic of the Khalsa, a manifestation of the sovereignty bestowed upon Sikhs, by Guru Gobind Singh.

THE HAWK OF NANAK-GOBIND TAKES FLIGHT AT DUSK

Guru Gobind Singh had passed from the world at Nanded, now Maharashtra, in 1708. (Refer to the tract – Last Days of Guru Govind Singh by Dr. Ganda Singh, Journal of Indian History, 1941. I will review this tract here soon.)

Among his final acts, was his founding of the political structure of Sikh Raj. ‘Sovereignty’, so to say, was bestowed upon the body of the Khalsa, as a whole, creating a Sikh body politic. This body politic was to be centred around the Sangat of the Adi Granth, now the eternal Guru. This was the culmination of the social regeneration commenced by Guru Nanak, symbolised by the founding of Kartarpur, and the commencement of a second phase of civilisational regeneration – the first phase, had continued in parallel with the evolution of the Sikh Sangat, as a multigenerational civilisation (re)building project, unfolding through the successor Mahals (Regencies) of the line of Gurus, following Guru Nanak. (This, too, is a subject of a forthcoming essay. For founding of Sikh Sangat see : Sangat and Society also by this author).

This essay is primarily focused on exploring the organisation of temporal power : the structure of Sikh polity. A broad outline of the structure of Sikh polity, created by Guru Gobind Singh is discussed below, proceeding from this axiom:

“Sovereignty resided in the body politic of the Khalsa Sikh.”

The root word of ‘khalsa’ can be translated as ‘purified’, but its meaning in a Sikh context is also understandable by looking at its application. It is important to understand what one is purified of. [The idea of purity in the Brahminical sense of the ‘twice born’ is completely rejected in Sikh theology.]

In the Mughal political order, the word khalsa was used to mark out land which was directly owned by the Emperor, that is which had no intermediary vassals. In the Sikh social structure, which since its inception was created to subvert Mughal claims of legitimate authority as rulers of their subjects – a Sikh owed allegiance not to the Mughal Emperor, who was identified as the false padishah, but to the one true ‘ruler’, the sacha padishah, which was, the infinite divine, or Akal Purakh, by whose true laws (hukum) the universe was ordered (hukum hovey aakar).

The use of khalsa for liberated Sikhs was therefore an etymological subversion of the Mughal Imperial structure,and claims to legitimacy. The Khalsa Sikh owed allegiance to the sacha padishah, and was therefore ‘khalas’ purified and liberated from the chains of unjust, anti-dharmic political authority. There is also perhaps an intentional territorial aspect to this meaning of khalsa. Was the Khalsa Sikh ‘created’ to make the territory controlled by the false emperor truly ‘khalas’ by deposing him, and destroying the edifice of unjust rule imposed by kings who were butchers (rajey kasai) and bring in an era of just rule (dharam raj) in a land where dharam had taken wings and disappeared (dharam pankh kar uddarya)? That is a question which must be explored.

While this might be the teleologic political purpose of the Khalsa, its spiritual connotation is equally important.

The vanishing of dharam in Sikh theology is not only a consequence of the rule of false kings, but also of the prevalence of false beliefs among the people of a land, indeed, of civilisations. When the venerable Bhai Gurdas wrote of Baba Nanak’s coming into the world – and his journey through it – as the coming of light and the lifting of fog, one of the implications was the lifting of the fog of superstition. The shabad says – jithé baba paer dharé puja aasan thaapan hoya; like all scripture of Sikhi, there are layers in every line (or even word) which can be unravelled to reveal a wealth of meanings, but one implications which comes to mind is that Bhai Gurdas has in mind the travels of Guru Nanak to Haridwar and Mecca, where through his actions he demonstrated the presence of the Divine in all things, and the ultimate Oneness of all things (gura ik deh bujhai – the guru helped us understand that all is one).

Now, the question is, how is man to know or comprehend infinity, or, how does the Guru take one on the journey to arrive at this understanding? In Sikh theology, the framework for human understanding of the infinite is – the Guru and the Shabad.

The Guru is, in a sense, a translator of the hukum of infinite into human language, that is the ‘shabad’, word of the guru. But, understanding comes to the human mind once it is able to imbibe the shabad in the mind, and, contemplate on it. [The value of contemplation, or simran, is a core Sikh practice.] There is, as one can see, stress on individual responsibility to understand the shabad of the Guru. By contemplating on the shabad, the intellect is sharpened, and the treasure of knowledge is attained.

[The shabad – mat(i) vich ratan jawahar manik je ik gur ki sikh suni is explored in the Faridkot Teeka (Exposition) as follows : when one listens to the guru, and begins to contemplate on the Oneness of all that exists (also see, above, shabad ‘gura ik deh bujhai), then the One is ‘revealed’ to the mind, as by listening to the seekh (teachings of the way) of the Guru one becomes in a true sense, a Sikh. The Teeka further proposes that by contemplating on the Truth of Oneness, the essence of that Oneness becomes established in the mind, and than the mind (or intellect) itself will itself reveal more treasures of the true knowledge. Such truths are likened to gems, the more one contemplates on this wisdom, the more gems are revealed attaching themselves to one another, like pearls in a necklace.]

As a Sikh became in a true sense Sikh only when the truth of Oneness became established in his mind, without any intermediaries [the Guru’s shabad being a ‘ship’ that takes one from ignorance to light], so, a Khalsa Sikh was subject to no intermediaries (false kings) on earth, but only to other Sikhs in whose mind the One is established. The Faridkot Teeka further makes a comparison of this realisation of Oneness in the intellect, to an ‘idol of a devta’ being established in a temple. (stapbhna), which then becomes the abode of the deva. For the Sikh, this realisation makes him one with Akal. [1. (The deathlessness of a Sikh is also evoked in his becoming Khalsa – he has stirred death into the holy Amrit and drank it, thus, becoming death himself.) 2. (The gurus ‘feet’, also wander through the mind of the devotee Sikh, one feels – perhaps contemplating on the travels of Baba Nanak is a form of self purifying meditation too. A devotee’s mind being in the guru’s feet – guru ke charan- too has many layers of meaning.)]

So, as, one does not need to travel to holy places to purify one’s soul, for, by traveling across the gulf of ignorance, by contemplating on the Gurus’s shabab, as the knowledge of Oneness becomes manifest in the mind, the mind itself becomes self-capable of redeeming itself – tirath naava je tis bhava.

From this follows an idea of self rule, or rule over the self, or swa-raja. From self rule over the mind, comes the self rule of the body, and when a community of such self-ruled minds and bodies come together, they create a body politic of the eternally free and unbound (cakravartini).

This was the Khalsa Sikh body politic, the foundations of which were laid in Kartarpur and which reached its teleological evolution in Anandpur.

THE KHALSA IN POST-GURU ERA

Till the time the Gurus walked the earth, the problem of organisation, leadership and consensus in a cakravartini body politic was an easy one to solve. The Guru was the Raja (regent of the sacha padishah) representing Dharam on the earthly realm. But how was the Sikh body politic to organise itself after the Gurus? Of course, as discussed above, the Khalsa as a whole was to be sovereign, but this still left the problem of creating structures for decision making and collective action.

These structures were also finalised by Guru Gobind Singh in his last days – (but they had evolved over years). There are two layers in this that I will restrict my exploration to, for now.

The first is the infrastructural layer of the Sikh religion: these are physical sites where the Sangat of the Guru is established. Sangat (Community) was a core around which Samaj (society) would be ordered. Samaj was ordered on what we might call a federated model of society, with federated units being concentric circles radiating outwards, each unit being a specialised Sampradaya (disciplinic subcommunity). This Sangat-Samaj-Sampradaya interface had evolved over generations, and needs broader discussion, which I will devote an entire essay to. (See Giani Sher Singh’s talk on Sampradaya and Samaj in Sikh tradition for more on this.) But this formed the social materiel of the Sikh polity.

The Khalsa body politic was to be the iron frame (in a literal sense and a metaphorical sense) to hold together the civilisational project which had unfolded itself around the Gurus over generations.

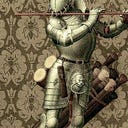

This was the crucial second layer, the concrete plaster on the edifice so to say, and the political order for this is revealed by the organisation of the first Khalsa Army, led by the Jathedar (General, or, Commander), Banda Singh Bahadur.

The Jathedar was in leadership command of the Khalsa Army, but he had a Council of Five Sikhs (Panchayat) appointee by Guru Gobind Singh, to advice and perhaps also to check his power. In addition to the Council of Five, was another selected body of twenty Sikhs, which we might call an Assembly. This basic structure of the Sikh polity was to have an overarching constitutional authority flowing from the Adi Granth, now, after Guru Gobind Singh, the Guru Granth Sahib. More specifically, this might be seen as an unwritten constitutional structure, which was to evolve through a set of ‘common law’ practices, decided through debate, arrived at through consensus – called the Guru-mata (ਗੁਰੂਮੱਤਾ) – a resolution passed in the presence of the Guru Granth Sahib.

This is how sovereignty flowed from the Guru to the Sangat, and from the Sangat, upward, through the ranks, across the entire structure of the body politic. Power and checks on power, flowed both ways. [If any appointee leader attempted to break this two way flow of power, he was going against the (unwritten) constitution of the Sikh ‘republican ideal’ – as, it happened, perhaps with Banda Singh Bahadur – a matter of debate – but most definitely with the ministers of the Lahore Durbar, as discussed by Maharaja Duleep Singh.]

This body politic was founded on what we might call a republican ideal, flowing from the understanding that all Khalsa Sikhs were equal as the Akal resided in each one of them. Indeed, the Khalsa as a body might be considered as the ‘12th’ Guru – a simplistic way of looking at it, but this is meant to indicate the unity of identity of all self realised Sikhs who has dissolved into the Akal, and had the Akal manifest in them.

CONCLUSION AS FOREWORD TO THE NEXT ESSAY

In this essay I have discussed both the philosophical reasons and the structure of the body politic of the Khalsa. And, explored how and why the Khalsa was organised to represent a Sikh ‘republican ideal’, born from the fundamental belief in self realised equality. I have discussed other important ideas too, such as the three forms of sovereignty : nonterritorial, territorial confederation, and kingdom-empire.

These are all variants of the organisation of the Sikh idea of the state (yes, there are more than one, and none of them close to a Wilsonian Ethnic State).

The 18th century in Sikh history is important because many of these forms both evolved and were experimented with in this era. This is something we will continue to explore.

–

Please subscribe to my newsletter to receive latest articles in your inbox : https://sialmirzagoraya.substack.com