A Day in the Life of Chander Bhan, Merchant of Lahore, Friend of Dara Shukhoh

Lahore, Summer, late 17th Century

As the white heat of the afternoon subdued the world into a still, solemn silence, Chander Bhan sat in the lower rooms of his palatial haveli, in a leafy Lahore neighbourhood, counting his precious scrolls, neatly arranged into clearly marked pigeon holes, on a wall at the end of the room. Dastan-i-Masih by Jerome, he murmured to himself, where did I get that one from. And what is it doing sitting above Prithvi Raja Raso.

The children must have moved it. He was not angry. He was pleased. They had been reading it! He was glad he had taught his granddaughters how to read – the twin joys of his old age. The only good that it had done Chander Bhan to have a son! A useless one. Ah! No! He was not so bad. He just didn’t share his old father’s passion for the written word. Not even for the great work of their illustrious ancestor Chand Bardai! A useless son.

But not as bad as Aurangzeb was to Shah Jahan! The memories poured over him; he was young, and there, in that corner, sat Dara, narrating a verse from… what Upanishad was it?

The son already called him half Musulman and now he couldn’t remember a darned Upanishad! But he remembered the shloka, he could hear it, as it was spoken in this room, long ago when Dara was Prince of Lahore, and his house was a gathering place of the wise.

‘Asato Ma Sad Gamaya, Tamaso Ma Jyotir Gamaya, Mrityor Ma Amritam Gamaya,’ the young prince said. ‘I believe the light is the same in both theologies, the eternal light of heaven, the light of immortality. Death is a gate through which we must all pass. To reach that light. To merge into the ocean of the infinite. Brahman. Allah. Light.’

Tears welled in his eyes. The Pathan had said they had led him through the streets of Delhi on an old, blind elephant’s back. The crowd had jeered him! Why did the crowd jeer him! Why was mankind so cruel to the kind among them! On the stairs of the Delhi Fort the sentence had been passed. They came, one by one, bare swords to kill him, the lion of Lahore, he fought them with his dagger for hours. His dagger! The ruby studded dagger. His, Chander Bhan’s gift to his dearest friend.

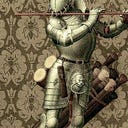

‘I am a rich merchant, Prince. Since your grandfather subdued the Uzbeks, convinced the hill Pathans to stay hidden in their mountain defiles, my caravans go far to Samarkand, to Tashkent even, unmolested. Badshah Akbar Jalal-ud-Din gave us peace in the Panchnad. A hard won peace. Accept this as a gift from the people of the five rivers,’ a beaming young man, standing in the high roofed chambers of the capitol hall of the Lahore Suba, purportedly welcoming the new governor on behalf of the Khatri merchants of the city, but completely immersed in the evocativeness of his own elocution, had said.

‘You speak Farsi well, Chander Bhan Ji. How good is your Punjabi?’ Dara Shukhoh had replied, laughing gently.

My Punjabi. My Punjabi. My forefather the great Chand Bardai invented Punjabi, Prince! Now where is my Diwan of Baba Fareed’s kafeeyan…

Then, another day, as the crimson sky cast its magic over Lahore’s evening skyline…

‘You know how that name came to be? A simple scout, a translator, he had been tasked to create a copy of a Moroccon traveller’s tales of Hind… he translated Panchnad, as Punj-Ab. My grand aunt, Gulbadan Begum, she was a lover of the written word like me. She liked the word, its sound, its… gentleness… and power. In her biography of the Emperor Humayun she used Punjab to refer to this land… I think the name will be remembered through the ages. Now, what is the surprise, my friend, a new wine from the lands of the Franks?’

Chander Bhan’s eyes gleamed as he remembered. How had he befriended the great man? When was it that the Prince had blessed the not so humble merchant’s house with his presence… a divine presence… was it? No, no. That he should not say.

‘No, my Prince, something finer than wine, more intoxicating, more invigorating. I read your words, the Majma-al-Bahrain… they moved me. Now, I am not a learned man like you… there is hardly a scroll in this house that is not numbers on a page, or inventory of stocks…’

‘This room would do well for a library. It is cool, below the ground, a good place for retiring in the afternoon,’ Dara Shukhoh said, as they retired indoors, not wanting to be seen consuming wine by strange eyes. ‘Now, as much as I love you my dear friend, do not keep me waiting.’

‘It is you who has kept us waiting, Prince,’ another voice, even sweeter than Chander Bhan’s own – how could it be! – had said.

With a tinge of envy, Chander Bhan had introduced the man. Baba Lal. A Brahmin, a Nath, a Sufi, a Fakeer… a man of no world, yet, knower of all the worlds beyond this world.

‘Now, I have a friend in Multan, Prince, a man from Ghazni, and he tells me you have written a book. The man with that naughty child for a son… little Najaf!’

The Mughal Prince, the one destined to be the Emperor of Hind, embraced the holy man. There, there they were, just hidden behind the veil of a few years, decades, there they were…

The Prince. His friend. Would the ages be kinder to him than his brother?

He had remained, wounded, still, bleeding on the stairs, for an hour, they say, refusing to die. He was chanting something. A kafir verse! A magic spell.

Chandar Bhan, the old man, whispered to himself: Asato Ma Sad Gamaya, Tamaso Ma Jyotir Gamaya, Mrityor Ma Amritam Gamaya.

Brihadaranyaka. That’s the one.

The crowds waiting, watching. Did some cry then? Did some realise what humanity had lost that day to ancient, fratricidal brutality? Finally, they said, Aurangzeb returned from his prayers, walked to his brother, and struck his own dagger into the Lion’s heart. Dara’s head was sent to Shah Jahan in a jewel studded casket. Chander Bhan wondered if it was the same casket in which Dara Shukhoh carried his scrolls. The old Emperor was lost in his drug drenched stupor. He did not weep. Only whispered, as he was prone to do all day – my crown, my crown. My taj, why did I kill you so…

There, there it was. The Dialogue of Dara and Baba Lal. The merging of the two oceans… it would happen, it would happen one day…

If it was not one Prince of Lahore, perhaps there would be another! A Prince of Lahore! Fancy that! Chander Bhan laughed aloud. He was an old man. An old man, too old.

There was a sound outside. Laughter and the tinkling of tiny bells. The children were awake. There were other sounds from the street outside. Lahore too was awake.

The spell of silence was broken.

Chander Bhan left the room, and his memories in the room below the old haveli, and walked into the daylight.

*