An Exegesis of Shiv Kumar Batalvi’s Orison to Guru Gobind Singh

The owl of Minerva takes flight at dusk. So did the hawk of Guru Gobind Singh.

Movement I

In Shiv Kumar Batalvi’s Orison (Aarti) of Guru Gobind Singh, we witness the reflection of a civilization looking at itself in mirror. Batalvi was the spiritual inheritor of the legacy of Bulleh Shah, the voice, like him, of a broken land. I say legacy, perhaps it would be better to say responsibility. Or burden. And it is a hard one to bear. When the rarefied thought of a culture speaks through the voice of a single mortal, if the vessel is not made of the strongest materiel, it will shatter. As Batalvi did. Bulleh Shah, despite his faith of being Allah’s own, cracked many times too under the weight, as is evident in some of his more melancholy verses. Faith in Allah, however, makes for a stronger man, than one who surrenders his to Bacchus. Bullah healed, Batalvi broke.

But in that broken mirror of his soul, he witnessed a civilisation’s progress – into what, remains to be seen. (I use the word progress only to signify movement in time, and attach no positive value to the word.)

–

In the 18th century, humanity had taken an inexorable leap. We began our transition from an agriculture based civilisation to a post-agriculture one : in some decades from now a significant quantity of our food will be purely lab grown. This will be an epochal transition: similar to the transition to agriculture from a hunting-foraging lifestyle made after the Younger Dryas, from around 9,000 years ago. The shift into an agriculture based civilisation changed humanity – fundamentally. It made us weaker, smaller and ultimately, domesticated, much like the animals we assume we keep but who, as it turns out, might be keeping us.

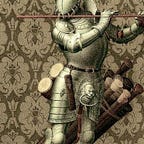

But in the long millennia that followed the founding of the first agricultural civilisations, humanity split into two forms of society: the domesticated life of the farming village, or the domus; and the life of nomad hunters, which I call the ordos. Some of the old wildness was preserved. It would be a terror to the tame, for ages to come.

For the people of the domus, the hordes of the ordos were barbarians. For the ordos, the domus were, as a Berber saying puts it, the fruits of their conquest : raiding, the Berbers said, was their agriculture. Raiding city walls, plundering treasuries and reducing the edifices of power was as natural to the warrior of the ordos as waking up in the morning and milking a cow was to the farmer of the domus. Their profession was to wipe the sneers of cold commands, reduce kingdoms to lone and level sands, to be lost in the deserts of time.

In Mesopotamian tradition, they were the Ummān Mandā, the wrath of god.

–

Movement II

In the Aarti of Shiv Kumar Batalvi, there is one resonant motif : the poet expresses his ‘weakness’ in the face of the ‘power’ required to even approach Guru Gobind Singh, let alone worship him, that is, to be one of his chosen.

Where does this sense of inadequacy come from? Is it merely the self admonishment of a love lorn alcoholic? None of Batalvi’s poems are an expression of his own pain – his life was a mere mask the poet constructed for the man; perhaps he did not understand it, but his poetry was a divine voice speaking in human voice, which to those who know how to listen can be hidden by no mask.

Much like Bulleh Shah, much like the rishis of Ancient Bharata, Batalvi was the voice of an age. In him, we see the culmination of a spirit of a passing age, as the poet reflects on the flight of the owl in night in a land still shrouded by the smoke of the fires of time.

To understand Batalvi’s motif of the pain of inadequacy, we must dig deeper into our exegesis of the poem itself. The Punjabi version is available here: https://punjabi-kavita.com/Aarti-Aarti.php. I will present some of my interpretation of his verses here.

–

Batalvi is a poet of tears. They were his fuel, pain was his engine. The poem begins :

[What lamp of tears shall I burn in adoration of you,

From which door shall I beg the alms of the Word,

Of which I can make an offering to you.

I have no song to sing for you,

None to rouse me, none to strengthen me to rise and offer my head to you.]

In this, and subsequent lines, Batalvi weaves in epochal moments from the life of Guru Gobind Singh. The glimmer of his light which strengthened the Beloved Five to offer their heads to the Guru (the Panj Pyaare); the martyrdom of the Guru’s young children who were tortured before being bricked alive in their refusal to submit to Islam; and evokes the hymn the Guru himself wrote in what would have been for a father, the most life shattering moment.

The hymn – mitr pyaare nu – evokes the Guru at his most human. In that it is not much different from the Baburbani of Guru Nanak.

For Batalvi, a man who carries his pain of a love shattered heart as the ordinary matter of a man living a life that is, naturally, a slow suicide – what else should it be – it is unimaginable that a man can bear such pain let alone harness it into a sword that would shatter an empire.

Mitr pyaare nu must be read alongside another scripture of the Guru – the Epistle of Victory, or the Zafarnamah, both for historical reasons and for the purposes of our exegesis – to understand the moment in time, the entire matter of the future of a millennia old civilisation rests in the spirit of a man. For in that moment, Guru Gobind Singh showed his Sangat how a father mourns for his children, so they too would know what it meant to be the children of Gobind Singh.

What would have been, for a father of young children, a moment of the greatest defeat, for the Guru became the song of the March of Victory. Against what? Against the depth of the darkness that pervaded the era of Kaliyuga. Against pain, against loss, against the death of hope.

The House of Nanak had been built at the dawn of the Reign of Darkness (kāl kānti, rājey kasāi), when the corruption had gathered into an insurmountable shadow, which had taken the blood of the most noble, the kindest and the most innocent, everyone who dared to dream of possibilities gradually gave way to conformity or was surrendered to death, like the noblest martyr of them all, Dara Shukhoh.

When for some, all hope was lost, then, at that moment of night, the Hawk of Guru Nanak took flight: the prophesied mard ka chela was given form by the mard agamra. The Khalsa was born, with rusted steel washed in blood.

–

So writes Batalvi :

[What song should I sing for you, I have none -

which can rise to your call, to offer my head for you,

a sacrifice which can with its blood wash the tarnished steel,

which demands that none shall mourn the death of one so called upon to perform the deed,

to become one who feels no pain, nor hesitates to deliver it upon his foe,

who is nourished by molten steel,

I have no such song from my soul to offer you,

not in my pain filled heart.

I have no song for you, no song –

that can wield the sword of truth,

to become one whose eyes are brilliant with wrath,

who desires nothing but death so he may mingle his blood with the soil of his land,

which is illuminated by the glory of the blood that too runs in you, that was spilled by the foe,

- how can I exalt you with my blood, shall such glory be tarnished by my coward blood?

- no, I have no song for you.]

As a matter of style, Batalvi’s voice is one of self effacement, a literary device used by Bhakti poetic tradition, which is employed by the devotee to destroy his own ego, to allow his self to destroy itself, so it can be gathered again to be re-formed by the light of its chosen lord.

Such a process of destruction and gathering is also evoked by Guru Nanak in the Baburbani: the psychological disintegration of the ego-ridden devotee and the coming together of his re-formed soul in the presence (through darsana) of the guru, resonates in history as much it does in the psychology or the poetry of the beloved. The destruction wrought by Babur’s armies in the greater Punjab were necessary precondition of history, so that a cycle of gathering of the Sikh Sangat could ensue. So is the psychological disintegration of the ego ridden man necessary for him to separate the detritus of Kaliyuga which has seeped into his mind, from the truth of illuminated self to shine forth (the light of the Akal resides equally in all men and women in Sikh theology, it only needs unveiling and gathering.) And so it is necessary for one who takes up the mantle of Khalsa, to destroy his self and mingle as one with timelessness.

Why does Batalvi feel he is incapable of approaching such illumination? Is it only his personal incapacity to rise to the purity of heroic action the illumination of Guru Gobind Singh demands – or is it then, the articulation of a subliminal strain caught by the poet’s mind of a defeated land and its exhausted people?

–

Movement III

The two forms of human society were in a relationship with each other similar to a predator and prey in trophic system. The ordos fed on the domus, in cyclical tends explored by numerous scholars, but nowhere explained better than by Ibn Khaldun in his Muqqadimah. The life of civilisation engenders decadence, it turns men into hedonic parasites or distraught automata, all cogs in a machine.

Perhaps it is not just that. Sun Tzu tells us that those who fight on the land of their homes are keener to surrender, for they have much more to lose than those who battle in far away lands.

So, it was perhaps in Indian history. The Arabs had been resisted for decades on the desert frontiers – they retreated, then they too ate the fruit of settled life. – but the Turks struck at the heart of the land and broke India’s back.

Perhaps resistance was futile, this history ess meant to unfold and the Turk was Ummān Mānda Reborn, a curse brought upon the heads of kings who had veered too far into the left handed path and their subjects who followed their swollen lords like sheep. Mongol blood made them stronger still, and a broken heart burnt with forbidden love, made Babur, a poet too, like Batalvi, warning us that such too can be the wrath of those wounded by the world.

When Babur descended on Hind with his marriage-party there were few to resist, except some Gujjars and Jats in whom traces of the old nomad blood was strong-flowing still. There was other hope, soon to be seen. As strong too was the long lost light of the sun chariot kings whose wheels had once turned unchecked from mountain to sea, not all Ksatriya blood was tainted in the darkening age, for some instead of hedonism had chosen industry.

In them there was preserved that honour still, a spark – which in the House of Nanak, was nurtured into a New Sun, which like the legends of old, gave birth to a new lineage of kings, Sons of the Sun, born again, to end the night.

–

chattr chakra vartee, chattr chakra bhugtay

Thou hast killed four Sons of my blood – Aurangzeb was told in the Epistle of Victory – for thy servants said them to be snakes; Behold from every drop of their blood another Son of Gobind is born.

A new sun had risen, the hunter became the prey, the Wrath of God was turned upon the Son of Babur, as peasants left their fields for the wilderness, and were reforged into world-roaming chakravarti warriors, the plunderers of thrones.

The shattering, the gathering, the thesis, the antithesis, light and darkness, blood and steel, the march of history, the Dawn of an Age. Everything happens for a reason.

The Reason.

For which everything is.

–

Overture

But what of the broken land? Who would make it whole? As had Batalvi, for himself a mask constructed, from the detritus of a love that could have been, so there were many who did the same, constructing false memories of ages that were not seen, but were only imagined – too poorly at that.

The honest few, like the poet, knew the broken could not be healed unless a reckoning was made. A purification of the word and the tongue.

For that is where Kaliyuga shows its stain most, in whom it still persists, so viciously in our times – in corrupted souls, with darkened tongues that spew venom as if that has become the only nature of man.

–

[The only desire of my heart, is to wash the detritus of filth that darkens my words,

To purify my tongue, so I can kiss your feet,

Wash them with my tears, and that will be my enlightenment,

So my heart might harden too,

That I can stand in your presence,

till then I had no song for you,

I have no song for you.]

-

suyumbhav subhang sarab dā sarab jugtay

dukhalang pranāsi dayalang saroopay

sadā ung sungay abhangang bibhootay ।

–